Independent News

“Alejandro Was Murdered”: Colombian Fisherman’s Family Files Claim Against U.S. over Boat Strike

This post was originally published on this site

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

The Pentagon has announced the U.S. blew up another boat in the eastern Pacific, killing four people, claiming the boat was carrying drugs, but once again offering no proof. This comes as the controversy continues to grow over the first U.S. boat strike September 2nd, when the U.S. targeted and killed two men who had survived an initial attack. Nine others were killed in the first strike September 2nd. The U.S. has now killed at least 87 people in 22 strikes on boats since September. The U.S. has not provided proof [of] the vessels’ activities or the identities of those on board.

But now the family of a fisherman from Colombia has come forward and has filed the first formal challenge to the U.S. military strikes. In a petition filed with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the family says a strike on September 15th killed 42-year-old Alejandro Andres Carranza Medina, a fisherman from Santa Marta, Colombia, a father of four. His family says he was fishing for tuna and marlin off Colombia’s Caribbean coast when his boat was bombed, that he wasn’t smuggling drugs. At the time, President Trump claimed the strike killed three narcoterrorists.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: We have proof. All you have to do is look at the cargo that was — like, it spattered all over the ocean, big bags of cocaine and fentanyl all over the place. And it was. Plus, we have recorded evidence that they were leaving.

AMY GOODMAN: A video released at the time shows a small boat exploding in flames.

For more, we’re joined in Pittsburgh by international human rights attorney Dan Kovalik. He filed the petition with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights on behalf of the family.

Welcome to Democracy Now! Explain what they are saying, Dan.

DAN KOVALIK: Thanks for having me, Amy.

Yeah, I mean, it’s pretty simple. The claim that the family is making is that Alejandro was murdered. You know, I was asked by one reporter, you know, “Was Alejandro innocent?” And, you know, my response was all these people who’ve been killed are innocent, because you’re innocent until proven guilty. None of these people were charged. None of them were put on trial and convicted. This is not how a civilized nation should act, just murdering people on the high seas without proof, without trial.

AMY GOODMAN: So, explain. Has the Trump administration gotten in touch? Has the Colombian government stood up for the victims of this boat strike? Has the U.S. government presented any evidence that, in fact, the person you’re representing, Andres Carranza Medina, was in fact a narcoterrorist?

DAN KOVALIK: No, the U.S. has presented no evidence. They have not responded at all to our petition. And in terms of the Colombian government, the truth is I got in touch with the family of Alejandro through the Petro administration, through President Petro of Colombia. So they are standing up to this. They are — actually, President Petro is creating a commission of lawyers to investigate more killings that have happened of Colombians in the Caribbean.

AMY GOODMAN: So, explain the response in Colombia to the killing of your client. You say in the petition the family has been threatened by right-wing paramilitaries for speaking out about Mr. Carranza’s death. Can you tell us more?

DAN KOVALIK: Yeah, well, you know, the sad thing is that right-wing paramilitaries, which the United States helped to create and helped to fund for many years, still exists in Colombia. And so, yeah, when the family came out publicly about the murder, they did receive death threats from right-wing paramilitaries. And in fact, they ended up being displaced as a result of these threats. But again, the government of Colombia is behind them, is supporting them. And there’s a lot of outrage in Colombia about these killings.

And what’s happened, by the way, Amy, is that, you know, again, fishermen are now stopping going out to sea to fish, because they’re afraid they’re just going to be blown up, which is — you know, makes sense. I mean, I wouldn’t go out there, either.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain what it means to bring a petition in front of the Inter-American Human Rights Commission. What is this commission? What power does it have over the United States?

DAN KOVALIK: Yes. Well, first of all, the Inter-American Commission is part of the Organization of American States. We brought the claims under the American Declaration for the Rights and Duties of Man, which is the oldest human rights instrument in the world. It was actually agreed to in Bogotá, Colombia, in 1948, even before the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was agreed to.

And the commission does have jurisdiction over the United States to investigate the United States for these types of crimes, which these are crimes, and to require the U.S. to respond to them. In the end, they will issue a report making recommendations, we hope, for compensation for the familiy, also telling the U.S. to stop these killings. In the end, you know, the U.S. could choose to disregard these recommendations, but we think, with a positive decision from the commission, combined with public pressure, which is building, that we can bring justice to this family and stop these killings on the high seas.

AMY GOODMAN: You filed the first formal complaint. Do you expect others to follow?

DAN KOVALIK: Oh, yes, we do, of course. And, you know, again, the Colombian government is reaching out, trying to find more families. And I am happy to take on more cases. I think this is one of the most significant human rights cases right now, certainly in the hemisphere, I mean, because it’s not just about, well, killings, but it’s about the rule of law. You know, it’s about the idea that you — that a government like the United States could just murder people based on mere accusations. As I say, it’s no different than, you know, going down the street here in Pittsburgh, and the cops saying, “Oh, I think that guy’s dealing in drugs,” and just blowing that person’s brains out.

AMY GOODMAN: Final question. We —

DAN KOVALIK: No one thinks that’s correct. You know. Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: We just have 10 seconds. Do you hold out —

DAN KOVALIK: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: — hope for the Senate investigation, both Republican and Democrat, raising serious questions about these bombings? Five seconds.

DAN KOVALIK: I am at least hopeful, Amy. Again, I think the tide is turning against these killings. The American public is disgusted by them. So, yeah, I think there’s hope.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to have to leave it there. Thank you so much.

DAN KOVALIK: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Dan Kovalik, international human rights attorney. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks for joining us.

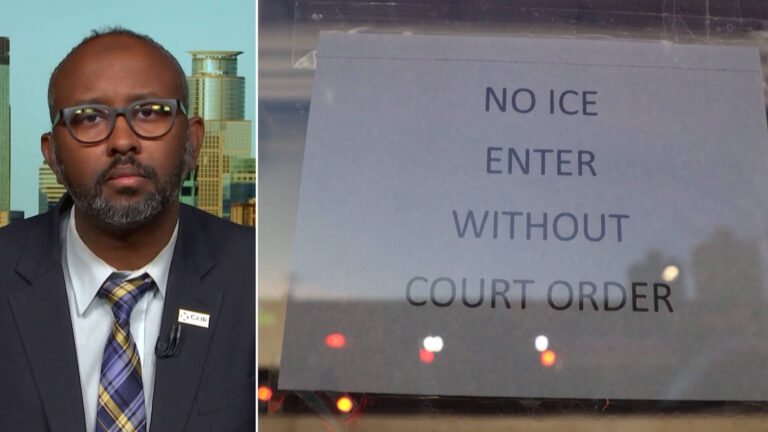

Trump Calls Somali Community “Garbage”: Minnesota Responds to Racist Rant and Immigration Sweeps

This post was originally published on this site

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: As we go from New Orleans to Minneapolis, we turn to Minnesota, where more than a hundred federal immigration agents are conducting operations this week, as President Trump escalates his attacks on the Somali community in the state. The Trump administration halted green card and citizenship applications from Somalis and people from 18 other countries after last week’s fatal shooting of a National Guardsman near the White House. One of those guardsmen died; another is fighting for his life. That was when an Afghan man who once worked for the CIA shot two members of the Guard.

During a Cabinet meeting Tuesday, Trump attacked the Somali community, making comments that were later widely condemned.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: I don’t want them in our country, I’ll be honest with you, OK? Somebody will say, “Oh, that’s not politically correct.” I don’t care. I don’t want them in our country. Their country is no good for a reason. Their country stinks. And we don’t want them in our country. I could say that about other countries, too. I can say it about other countries, too. We don’t want them to hell. We’ve got to — we have to rebuild our country. You know, our country is at a tipping point. We could go bad. We’re at a tipping point. I don’t know if people mind me saying that, but I’m saying it. We could go one way or the other. And we’re going to go the wrong way if we keep taking in garbage into our country. Ilhan Omar is garbage. She’s garbage. Her friends are garbage.

AMY GOODMAN: President Trump’s comments at a Cabinet meeting on Tuesday.

Congressmember Ilhan Omar, a Somali American, first refugee congressmember, called President Trump’s comments and his obsession with her, as she described it, “creepy,” said, “He needs help.”

Trump made similar remarks on Wednesday. On Thursday, Democratic Minnesota Governor Tim Walz called Trump’s racist tirades “dangerous.” He also noted the vast majority of Somalis who live in Minnesota are American citizens and legal permanent residents.

GOV. TIM WALZ: It appears very little is being done. They bring these folks in from Texas or somewhere like that. I’m sure they’re too cold to get out of their cars to harass people. But they’re doing it in New Orleans. It’s all about show. It’s not about — they demonize an entire group, potentially 60,000 people, based on racial profiling. There are only about 300 people with the protective status that were here.

AMY GOODMAN: For more, we’re joined in Minneapolis by Jaylani Hussein, executive director of CAIR — that’s the Council on American-Islamic Relations.

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Jaylani Hussein. If you can start off by responding to President Trump’s comments, calling the Somali community “garbage” and singling out Ilhan Omar, calling her “garbage,” as he said that they should leave the country? You were born in Somalia. You came to the United States as a child. Can you talk about the danger this puts you in when the president of the United States talks about an entire community in this way?

JAYLANI HUSSEIN: Well, I think it’s extremely — thank you for having me.

I think it’s extremely disappointing. And especially, I think Americans across this country should be abhorred. And most importantly, you know, we understand why we’re being attacked. We believe it’s actually because of our success. Somali Americans have been in the United States now for more than 30 years. We came here partially because of our refugee status, and the doors were actually opened by George Bush Sr.

And, you know, the fact that this attack is happening to this community, and continues to happen, we believe, is because of the fact that we fill the three — trifecta. We are a Black immigrant, and we know that President Trump continues to attack Black people, whether they’re descendants of slaves here in the United States or African immigrants. We see the majority of the countries that have been banned are African. Also the fact of immigrants and, of course, being a Muslim. And I think those trifectas continue to make it easy to scapegoat.

We know that there are foreign entities that want — including Israel, as well as the Hindu extremists in this country, who want to reverse the course of what is actually taking place in this country, which is for the first time Republicans waking up to these wars, to these never-ending wars, and the carnage of what happened in Gaza. And so, we know that that’s an element as part of the reason why this community is being targeted. But here’s what I’ll tell you —

AMY GOODMAN: You’re saying because it’s a largely Muslim community, Jaylani?

JAYLANI HUSSEIN: Yes, absolutely. And I think that, you know, there is an effort to try to demonize Muslims. This has always been the case. If you demonize Muslims, then you can get away with killing Muslims abroad. This has always been the case, from the Afghanistan War to the Iraq War. We know that.

And I think many young Republicans and many, obviously, progressive Democrats and Democrats across this country, and perhaps the future of this country, do not want to have a government that spends majority of its time in wars of killing other people and not taking care of Americans here. I think that’s at the center of it.

However, you know, it’s been interesting to have these hundred-plus ICE agents descend on our state. And so far, what we’ve heard is, literally, them detaining U.S. citizens. I think that yesterday we learned that they maybe only picked up five Somali Americans who are going through the immigration process.

AMY GOODMAN: I’m wondering if you could also comment on what happened in November, Texas Republican Governor Greg Abbott declaring your organization, the Council on American-Islamic Relations, CAIR, the country’s largest Muslim civil rights group, a foreign terrorist organization. It’s not even clear that he has the ability, as a governor of a state, to classify an organization in this way.

JAYLANI HUSSEIN: I think it’s the — I think it fits the same pattern of behavior that we have seen, where Israeli-first politicians are doing the bidding of Netanyahu. We know that CAIR has actually had a spy who had connections to the Netanyahu government, who infiltrated one of our CAIR chapters. We are the largest civil rights organization. It is because of the fact of how effective we are in ensuring the rights of American Muslims and others that we’ve become a target for these groups. And so, you know, it’s been widely condemned. And the reality is, is this is where they go. You know, this is kind of the targeting that we have seen, and we expect that. And perhaps there will be even more.

But it’s falling, I believe, on deaf ears, because more and more people are reading now, more and more people are awake, and there’s a younger generation of Americans I am really hopeful will not be duped by the same type of rhetoric that we have seen in the past.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you have the largest Somali American population in the United States in the Twin Cities, Minneapolis-St. Paul, around what? Eighy-four thousand people, with approximately three-quarters, 73%, of Somali immigrants being naturalized citizens. This is imperiling Republican candidates and political figures. I have seen people concerned about whether they will be elected. There are Somali Republicans and Democrats. I saw a father and business owner yesterday saying he voted for Trump. How does he talk to his children about him calling — Trump calling his children “garbage”? But if you can talk about the citizenship and President Trump threatening to take away, if this is even in his power, reexamine naturalized citizens?

JAYLANI HUSSEIN: Yeah, I mean, these threats have been there. It’s part of their plan. I know that we estimate about 58%, or a little more than that, of Somali Americans are actually born here. So we have a pretty young community. And about almost 80%, actually — we have some higher numbers of those who are either lawful residents or majority being U.S. citizens. We’ve been here for 30-plus years. We have built ourselves to be a fabric of this great state of Minnesota, not only in the urban core, but in greater parts of the state. And so, yeah, these efforts to try to do that is interesting, but it is part of this effort to try to, again, target immigration in this country. And I believe it’s not only racist, but it’s a plan that is to kind of respond to that kind of white nationalist effort that we have heard for so much.

To the other point, politically, you know, Somali Americans, just like any other community, are not monolithic. You know, we have seen actually a sharp increase of Somali Americans supporting Republicans in the state of Minnesota, including President Trump. And there are many of them. Some have publicly declared that they are out of the Republican Party, and others are asking hard questions.

And here’s the interesting thing: You know, the Republican leadership in the state of Minnesota understand what is happening. In fact, you know, they are kind of right now silent and not choosing to come up and say, you know, these — our community, the Somali American community, and many who even voted for them, are not garbage, and the president was out of line.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you tell your own story, Jaylani Hussein, how you came to the United States from Somalia?

JAYLANI HUSSEIN: You know, this is one thing that I think people don’t understand. You know, as an immigrant child or refugee child, nobody wants to leave home. I never, as a young child, ever imagined leaving anywhere. I remember living next to the airport, and I would see planes leaving. And, you know, as a child, you might have wanted to get on a plane and see things, but home is always home.

And because of that civil war — which I hope we get a chance sometime to talk about that, because people don’t realize how United States foreign policy plays into destabilization, including my own country, because Somalia was part of the Cold War, that the United States and Russia interfered with our own government and created us to have wars with our neighbors in Ethiopia.

But I left Somalia as a child, and I came here to Minnesota. And my father always says that, you know, we came to one of the coldest places, but we found people with warm hearts. And today, you know, I’m as Minnesotan as you can get.

And there’s something unique about Minnesota. Minnesota also has a large number of other immigrants, including folks from Laos, the Hmong population, and as well as a large other Latino and South American community. And it’s interesting. You know, it’s starting to be really unique. And for those who have visited us here in the state of Minnesota would find that, you know, robust diversity that is growing in the heart of the Twin Cities.

But Minnesota has not only embraced Somali community, but, you know, you start to see that our food and the things that we do are also part of the growth of the state. And so, you know, I was just joking to reporters that I was in a deer stand a couple of weeks ago, even though I didn’t get a deer. And that’s what it is. You know, when we come together and we live in this great country and try to make it even a better country, that is really the story of the immigrant community.

And that’s something that is not only hopeful, but in this moment, we are really asking, especially Minnesotans and folks across the country, to speak up. And I know and I’ve heard from Republicans, individuals. I’ve heard of so many people who are not only shocked and dismayed by what the president has said. And yesterday, we had faith leaders who spoke up. And many other community members are speaking up. And yesterday, we also called for a national day of action on Saturday, December 13, for folks to speak up across this country, to stand with Somali Americans, but also other immigrants in this country.

You know, this is a Native land. And other than the forced enslavement of African Americans, everyone else has really an immigrant story. And that’s the story we need to tell. And, you know, I hope this message goes to, you know, Melania. I know she is an immigrant herself. And I think she, in this moment, could potentially speak to the president and maybe even present a different story to the president.

Demonizing an entire community for the act of individuals is wrong. I also think, for many people who are asking these questions, you know, this is the oldest story, using crime to define a community. This is what media has done. They constantly lead with crime, and subjected without really giving it nuance. And that’s why today we have one of the largest mass incarceration of people of color, even though crime doesn’t have race or anything else.

So, this is a moment, I think, for our nation. We have seen vile things that the president has said, but in these moments, we need to come together and respond. But I also am asking for people to know, especially those on social media today who are projecting this hatred toward the Somali community — we believe some of those people are actually acting on behalf of foreign governments, and we need those individuals to be investigated, and if they are acting for a foreign government, they need to register in that manner.

AMY GOODMAN: Jaylani Hussein, I want to thank you so much for being with us, executive director of CAIR-Minnesota — that’s the Council of American-Islamic Relations — born in Somalia, came to the U.S. as a child.

As the U.S. blows up another boat, this one in the Pacific, and senators watch video of two September strike survivors clinging for life to a boat for more than 40 minutes, countering Secretary Hegseth’s claims of “fog of war,” we’ll speak with the lawyer for the family of another boat strike, this one a Colombian father of four. The family is challenging the strikes. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Wa Ana Amshi,” “As I Walk,” written by the Lebanese musical composer Marcel Khalife, performed here in New York at a Gaza benefit, NYC Palestinian Youth Choir this week.

Rigging Democracy: Supreme Court Approves Racial Texas Gerrymander, Handing Trump Midterm Advantage

This post was originally published on this site

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: A major victory for President Trump: The Supreme Court has cleared the way for Texas to use a new congressional map designed to help Republicans pick up as many as five House seats in next year’s midterms. A lower court previously ruled the redistricting map was unconstitutional because it had been racially gerrymandered and would likely dilute the political power of Black and Latino voters.

Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan wrote in her dissent, quote, “This court’s stay ensures that many Texas citizens, for no good reason, will be placed in electoral districts because of their race. And that result, as this court has pronounced year in and year out, is a violation of the constitution,” Justice Kagan wrote.

For more, we’re joined by Ari Berman, voting rights correspondent for Mother Jones magazine. His new piece is headlined “The Roberts Court Just Helped Trump Rig the Midterms.” Ari is the author of Minority Rule: The Right-Wing Attack on the Will of the People — and the Fight to Resist It.

Ari Berman, welcome back to Democracy Now! Talk about the significance of this Supreme Court decision yesterday. And what exactly was Samuel Alito’s role?

ARI BERMAN: Good morning, Amy, and thank you for having me back on the show.

So, the immediate effect is that Texas will now be able to use a congressional map that has already been found to be racially gerrymandered and could allow Republicans to pick up five new seats in the midterms. And remember, Texas started this whole gerrymandering arms race, where state after state is now redrawing their maps ahead of the midterms, essentially normalizing something that is deeply abnormal.

It was an unsigned majority opinion, but Samuel Alito wrote a concurrence, basically saying that the Texas map was a partisan map, pure and simple. And remember, Amy, the Supreme Court has already laid the groundwork for Texas to do this kind of thing by essentially saying that partisan gerrymandering cannot be reviewed in federal court, no matter how egregious it is. They have blocked racial gerrymandering in the past, but now, essentially, what they’re allowing to do is they’re allowing Texas to camouflage a racial gerrymander as a partisan gerrymander, and they’ve given President Trump a huge victory in his war against American democracy.

AMY GOODMAN: This overturned a lower court ruling. What are the role of the courts now, with the Supreme Court ruling again and again on this?

ARI BERMAN: Well, basically, what the Supreme Court has done is it’s given President Trump the power of a king, and it’s given itself the power of a monarchy, because what happens is lower courts keep striking down things that President Trump and his party do, including Trump appointees to the lower courts — the Texas redistricting map was struck down by a Trump appointee, who found that it was racially gerrymandered to discriminate against Black and Latino voters. What the Roberts Court did was overturn that lower court opinion, just as it’s overturned so many other lower court opinions to rule in favor of Donald Trump and his party.

And one of the most staggering things, Amy, is the fact that the Roberts Court has ruled for President Trump 90% of the time in these shadow docket cases. So, in all of these big issues, whether it’s on voting rights or immigration or presidential powers, lower courts are constraining the president, and the Supreme Court repeatedly is saying that the president and his party are essentially above the law.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you have talked about the Supreme Court in 2019 ruling in a case, ordered that courts should stay out of disputes over partisan gerrymandering. Tell us more about that.

ARI BERMAN: It was really a catastrophic ruling for democracy, because what it said is that no matter how egregiously a state gerrymanders to try to target a political party, that those claims not only can’t be struck down in federal court, they can’t even be reviewed in federal court. And what that has done is it said to the Texases of the world, “You can gerrymander as much as you want, as long as you say that you’re doing it for partisan purposes.”

So, this whole exercise made a complete mockery of democracy, because Texas goes out there and says, “We freely admit that we are drawing these districts to pick up five new Republican seats.” President Trump says, “We’re entitled to five new seats.” Now, that would strike the average American as absurd, the idea that you could just redraw maps mid-decade to give more seats to your party. But the Supreme Court has basically laid the groundwork for that to be OK.

And even though racial gerrymandering, discriminating against Black and Hispanic voters, for example, is unconstitutional, which is what the lower court found in Texas, the Roberts Court continually has allowed Republicans to get away with this kind of racial gerrymandering by allowing them to just claim that it’s partisan gerrymandering. And that’s what happened once again in Texas yesterday.

ARI BERMAN: Where does this leave the Voting Rights Act? And for people, especially young people who, you know, weren’t alive in 1965, explain what it says and its importance then.

ARI BERMAN: The Voting Rights Act is the most important piece of civil rights legislation ever passed by the Congress. It quite literally ended the Jim Crow regime in the South by getting rid of the literacy tests and the poll taxes and all the other suppressive devices that had prevented Black people from being able to register and vote in the South for so many years.

It has been repeatedly gutted by the Roberts Court, which has ruled that states with a long history of discrimination, like Texas, no longer have to approve their voting changes with the federal government. The Roberts Court has made it much harder to strike down laws that discriminate against voters of color. And now they are preparing potentially to gut protections that protect people of color from being able to elect candidates of choice.

And I think the Texas ruling is a bad sign, another bad sign, for the Voting Rights Act, because a lower court found that Texas drew these maps to discriminate against Black and Latino voters, that they specifically targeted districts where Black and Latino voters had elected their candidates of choice. And the Supreme Court said, “No, we’re OK with doing it.” So it was yet another example in which the Supreme Court is choosing to protect white power over the power of Black, Latino, Asian American voters.

AMY GOODMAN: So, where does this leave the other cases? You have California’s Prop 50 to redraw the state’s congressional districts, but that was done another way. It was done by a referendum. The people of California voted on it. And then you’ve got North Carolina. You’ve got Missouri. Where does this leave everything before next midterm elections?

ARI BERMAN: Yeah, there’s a lot of activity in the courts so far. A federal court has already upheld North Carolina’s map, which was specifically targeted to dismantle a district of a Black Democrat there. The only district they changed was held by a Black Democrat in the state. In Missouri right now, organizers are trying to get signatures for a referendum to be able to block that district, which also targeted the district of a Black Democrat, Emanuel Cleaver.

California’s law is being challenged by Republicans and by the Justice Department. The Supreme Court did signal, however, in its decision in Texas that they believe that the California map was also a partisan gerrymander, so that that would lead one to believe that if the Supreme Court is going to uphold the Texas map, they would also uphold the California map.

And we’ve also seen repeatedly that there’s double standards for this court, that they allow Republicans to get away with things that they don’t allow Democrats to get away with. They’ve allowed Trump to get away with things that they did not allow Biden to get away with. But generally speaking, it seems like the Supreme Court is going to allow states to gerrymander as much as they want. And that’s going to lead to a situation where American democracy is going to become more rigged and less fair.

AMY GOODMAN: Ari Berman, voting rights correspondent for Mother Jones magazine, author of Minority Rule: The Right-Wing Attack on the Will of the People — and the Fight to Resist It. We’ll link to your piece, “The Roberts Court Just Helped Trump Rig the Midterms.”

Next up, immigration crackdowns continue nationwide. We’ll go to New Orleans, where agents are expected to make 5,000 arrests, and to Minneapolis, as Trump escalates his attacks on the Somali community there, calling the whole community “garbage.” Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Ounadikom,” “I Call Out to You,” composed by Ahmad Kaabour at the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975 and performed at a Gaza benefit concert on Wednesday by the NYC Palestinian Youth Choir.

West African Asylum Seekers Find Safe Haven in NYC Volunteer-Run Kitchen

This post was originally published on this site

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s turn to a story right here, not far from Democracy Now!‘s studios. As New Yorkers protest escalating ICE raids in the city, some are also volunteering to support newly arrived migrants and asylum seekers, including those from West Africa. I want to turn to a report by Democracy Now!‘s Messiah Rhodes.

MESSIAH RHODES: We’re here in front of Plado, where Cafewal weekday kitchen provides over 150 meals a day. With its origins in supporting West African migrants escaping political oppression and violence from their home country, as well as the violence of colonialism as they journey to the United States, Cafewal provides a warm meal and a safe haven for West African migrants just newly arriving in New York City.

TYLER HEFFERON: So, my name is Tyler Hefferon. I’m the executive director of EVLovesNYC. We are a organization founded back in 2020 with a mission to fight food insecurity all over New York City. In our third year of operations, we started to work with a lot of refugee and asylum seeker populations coming through the city-run St. Brigid migrant reticketing center in the East Village. And at that point, we began to meet a lot of asylum seekers from West Africa who were coming over as single adults to seek asylum from their respective countries.

So, from there, what we started to do is we opened a volunteer program focused on asylum seekers to get them the letters they needed to stay in the New York City shelter system. That began in Ramadan of 2024, where we invited the handful of people that we had been meeting on a close basis to come into our kitchen and prepare authentic West African meals. They just sent us the ingredients. They knew all the recipes by heart, and it was some of their favorite childhood dishes from back home. So, it was a really fun week where every night we would prepare a iftar meal for a different mosque or community organization serving hundreds of New Yorkers who were observing fasting during Ramadan. And that sort of began this impromptu restaurant training program.

About six months later, we founded a full-time kitchen called Cafewal, which means “cafeteria” in the Fulani language. That’s developed to a fuller-scale workforce training program, where the hope is that the people that are getting paid wages to work in our kitchen are getting ready to work in some of your favorite restaurants around New York City. So, we work with different mutual aids, like East Village Neighbors Who Care, to help them with the different supporting services, like English lessons, résumé writing, job applications, all those different supports that we take for granted here as citizens, in addition to the workforce training that they’re receiving in the kitchen every day.

ABDUL KARIM: My name is Abdul Karim. I’m from Guinea. I have been in the Cafewal seven months. I’m cooking here rice and chicken, the salad, the potato.

MESSIAH RHODES: What future do you see in the United States?

ABDUL KARIM: I’m not to come here for looking for money and something. I’m come here for help the people here. When I help the people here, the people will help me one day.

DIAMY BAH: I’m Diamy Bah. It was back in January 2024, I was just trying to find a place where it’s warm, because it was cold at that time. So, at Tompkins Park, they told me about Earthchxrch. It was a warming center for everyone. So I went there, and, you know, I see how the East Village Neighbors Who Care was taking care of the guys. So I was very impressed. And then I proposed myself to be volunteer.

MESSIAH RHODES: Can you talk about the role of interpreters, how interpreters are a part of Cafewal when it comes to the language barrier?

DIAMY BAH: Oh, yeah. For the interpreter, it’s the good thing, because a lot guys here, they didn’t go to school. They just speak Fulani, and it’s very difficult for them to speak English. So, they are very confident to see the guys from their country and speaking their own languages. And to be an interpreter, they are very confident and comfortable to talk about their problem, even it’s very privacy. So, they do a lot of jobs here. So I’m so happy to have them alongside me to help and to continue to run Cafewal.

BRIAN DUGGAN: My name is Brian Duggan. I’m an attorney, and I volunteer for not-for-profit organizations like Cafewal and also provide “low bono” services for and pro bono services for some of the asylees here.

MESSIAH RHODES: Why is it harder for West African migrants to find legal representation compared to others?

BRIAN DUGGAN: Yes, well, it’s very difficult because of the language barriers in a lot of ways, but also because the system itself is so swamped with people applying for asylum, and there’s a low capacity for legal support, and a lot of attorneys require a lot of money up front, which these people are unable to provide. So they rely on a lot of people to provide pro bono services, pro se services, which are self-help-type services, and attorneys such as myself who try to provide low-cost services for them, so they can at least have some support at the hearings.

MESSIAH RHODES: And what countries do you commonly see people come from? And what are they usually escaping from, that you’ve seen?

BRIAN DUGGAN: The countries I’ve been associated with mostly are West Africans. Guinea is one of them, Morocco and also Mauritania. Those three areas have a lot of issues with their government, especially Guinea and Mauritania. They have government control, and most of the asylees here are refugees as ethnic refugees because they belong to an ethnic group called the Fulani, who have been persecuted by the powers in — that are comprised of another ethnic group, the Malinke. And so, historically, since France left Guinea, the government’s been occupied by one dictator after another, and they’ve always persecuted the Fulani. The Fulani make up the largest population, but they’re usually the targets of most of the violence. The government treats them and persecutes them with impunity. They beat them regularly. They have what they call enforced disappearances, where they are taken away from their homes and the families don’t know where they are, and usually have no opportunities to reclaim their bodies after they’ve found out that they were dead. This goes on all the time, and there is no recourse, doesn’t seem to be any kind of pressure for this to abate. So, this results in a lot of refugees coming to the United States.

AMY GOODMAN: Special thanks to Democracy Now!’s Messiah Rhodes, Safwat Nazzal and Robby Karran for that report.

On Tuesday, I got a chance to ask New York Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani about protecting workers from ICE.

AMY GOODMAN: Zohran, can I ask a question about — many of the workers in this city are immigrants. When you met with President Trump, did you get a concession from him around ICE raids and not moving into this city?

MAYOR–ELECT ZOHRAN MAMDANI: When I met with the president, I made very clear that these kinds of raids are cruel and inhumane, that they are raids that do nothing to serve the interests of public safety, and that my responsibility is to be the mayor to each and every person that calls this city their home, and that includes millions of immigrants, of which I am one. And I am proud that I will be the first immigrant mayor of the city in generations, and prouder still for the fact that I will live up to the statue that we have in our harbor and the ideals which we have long proclaimed as being those of the city, but which have too often been ones we do not actually enforce and celebrate on a daily basis. And that is who I will be as the mayor of this city.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani, standing with Senator Bernie Sanders. They were walking the picket line with Starbucks workers, who are also going to stage another protest today at 1:00 in front of the Empire State Building. Murad Awawdeh, you are serving on the transition team of the mayor-elect, and the mayor, you’ll be advising him. As you listen to that report of groups that are serving the West African community, and this whole question of how the city will be working with or against the president when it comes to ICE raids, what kind of protection do people have? And what can Mayor Mamdani do?

MURAD AWAWDEH: Well, the first thing is, having a mayor who’s actually going to stand up and fight for New Yorkers is a amazing feat to have in this moment.

The other piece is that we already have numerous sanctuary policies on the books, which the current administration has been running afoul and which DOI, the Department of Investigation, released yesterday a report of several instances where they had to investigate and saw that there was some efforts of collusion from pro-Palestine activists to an NYPD officer going rogue and assisting ICE agents. So, we want to make sure that anyone who’s working for the city of New York is abiding by local laws, including NYPD, DOC and all city agencies. So, an audit of every agency and their communication is absolutely necessary, and then training workers to be able to understand that your job is not to harm and, you know, contribute to family separation or hurting our communities in our city, but it’s to actually uplift all New Yorkers.

Additionally, investing in immigration legal services. You heard the lawyer from EVLovesNYC, which is an amazing member organization of ours that serves thousands of people every year. A big issue is that we don’t have enough immigration lawyers, and we need additional immigration legal services funding from the city of New York.

So, making sure that we’re following the laws that we currently have on the books, expanding where we can, and then making sure that we’re investing in our communities. Forty-three percent of all workers in New York City are foreign-born. Forty-three percent. Fifty percent of small businesses are immigrant-owned, as well. So we need to make sure that we are ensuring that the safety and security of all these folks is protected by the city of New York.

AMY GOODMAN: We just have 30 seconds, but we wanted to ask you about this Chinese father and son, 6-year-old son, the father named Fei, the 6-year-old named Yuanxin, who were picked up by ICE, the father sent to an ICE jail. The son, the 6-year-old, no one knows where he is.

MURAD AWAWDEH: The father is currently in Orange County in detention. The son is in OR custody, which means that’s where normally children who are unaccompanied — which is not the situation with this family. The Trump administration is continuing their family separation agenda, and we need to fight back against that, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: Murad Awawdeh, thanks so much for clarifying that, president and CEO of the New York Immigration Coalition, part of Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani’s Committee on Immigrant Justice.

That does it for our show. Tonight, I’ll be in Sag Harbor on the East End of Long Island, where there will be a 7:30 screening of the film Steal This Story, Please!, about Democracy Now! It’s at the Bay Street Theater in Sag Harbor. I’ll be doing the Q&A afterwards with the filmmakers, Tia Lessin and Carl Deal. Check out our website at democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh. Thanks for joining us.

“Making America White Again”: Trump Further Restricts Immigration, Ramps Up ICE Raids

This post was originally published on this site

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: We look now at the escalating crackdown on lawful immigration pathways, as the Trump administration has announced it’s pausing green card and U.S. citizenship processing for immigrants from 19 non-European countries that were already subject to a travel ban put in place earlier this year.

This comes as federal immigration agents have reportedly begun operations targeting the Somali community in the Minneapolis-St. Paul region. The Trump administration’s announcement has also paused all asylum decisions for immigrants currently in the U.S., after an Afghan national was charged with murdering a National Guard member and critically injuring another in Washington, D.C., last week. He’s pleaded not guilty.

AMY GOODMAN: For more, we’re joined by Murad Awawdeh, president and CEO of the New York Immigration Coalition, part of Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani’s Committee on Immigrant Justice. In a moment, we’re going to ask you about what’s happened here in New York with attempted ICE raids thwarted by the community. But first, let’s talk about exactly what President Trump is talking about when he says he’s going to stop immigration from the, quote, “Third World,” and what real-life effects is this having.

MURAD AWAWDEH: So, Donald Trump has made several horrendous allegations against immigrant communities, especially in the wake of the unfortunate and devastating incident in D.C., where he is saying now that they are going to be pausing all asylum applications and reviewing those who had been approved under the previous administration, as well.

The problem with that is that asylum and refugee status are some of the most — the hardest statuses to attain. The amount of vetting that you have to go through is insane in itself, but also it’s a very diligent process. So, for them to say that they’re pausing all asylum claims, that they’re going to be reviewing all refugees who have come into this country, and now saying that they’re going to pause and, in essence, ban all Black, Brown and anyone who isn’t white from coming into the United States, just is another slap in the face of the communities that continue to make this country move forward, the economic engine, the heartbeat of this nation.

So, what we’re going to see is millions of families who have been waiting, following the process, following the law to the letter of it, who are waiting for their families to be reunited with them here, pretty much having to be left in limbo, not knowing if they’re ever going to get connected with each other again.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And do you know, like, on what grounds? I mean, apart from just a presidential whim. Has he, first of all, chosen those 19 countries? And, you know, has anything like this ever happened here before, like an outright suspension of consideration of these applications?

MURAD AWAWDEH: There has been. Under Trump 1.0 —

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Yes, of course.

MURAD AWAWDEH: — he did this, and almost immediately after coming into office. It was sued several times. And, in essence, what happened was the ban was in part struck down, but then also upheld by the Supreme Court, because saying that the executive had the power to do so.

This is different, though. They’re doing this along a different route, where they’re trying to say this is going to be a temporary measure to ensure that they are, quote-unquote, “fully vetting” individuals who are coming into this nation.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And people are already reporting that they’ve appeared for green card interviews and U.S. citizenship ceremonies, and they’ve been turned away without explanation. They didn’t even know that their appointments were canceled. What kind of recourse do people have now? I mean, this is an extraordinary move.

MURAD AWAWDEH: This is really — imagine going through a process that can take up to 10, 15, 20 years, and then, at the very end, when you are about to become a naturalized U.S. citizen, who has contributed to this nation, who has continued to build your family here, built your life here for decades, and then, at the last second, being told, “Get out of the line. You’re not allowed to get naturalized today,” or even families who have waited forever to actually get their appointment to have their family come in for a green card interview, and either being rejected and saying your appointment has been canceled or that the person is getting detained and being put through deportation proceedings, which is also happening.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And even to get a green card, as indeed someone who’s gone through the process, there is an extraordinary amount of vetting that takes place and an extraordinary amount of paperwork. And after that vetting, it takes five years to get citizenship. Like, what more vetting is even possible to do?

MURAD AWAWDEH: It’s just, you know, lunacy at this point of the excuses that they keep coming up with, when we know what they’re trying to do. This has never been about vetting. This has never been about security and safety. It’s about cruelty, and that’s their point. And they’ll continue to lean in on their cruelty, and we have to continue to fight back.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to just name those countries, 19 countries, that they are stopping processing for, and they’re already talking about adding a number of other countries to this: Afghanistan, Burma, Chad, Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Haiti, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Yemen, Burundi, Cuba, Laos, Sierra Leone, Togo, Turkmenistan and Venezuela.

MURAD AWAWDEH: Yeah, these are similar countries that he tried, initially, putting the full ban, the partial ban, and then more restrictions on, when he first came into office and saying that he was going to do the same that he did the last time around. So, this is sort of using the same trick out of the same toolbox of trying to just harm more communities across this country.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And if there were any doubt about what the actual intention of the Trump administration appears to be, he’s actually said specifically that the U.S. should welcome more people from countries like Norway, Denmark and Switzerland, in addition to, of course, his special fondness for Afrikaners in South Africa, from South Africa.

MURAD AWAWDEH: Well, we don’t have to guess why he’s saying this. He wants to make — and his entire anti-immigrant platform, his war on immigrants and his mass deportation agenda is all to lead to making America white again. And that is what it comes down to.

AMY GOODMAN: So, let’s talk about the resistance. Here in New York on Saturday, police arrested a number of protesters after people blocked the exit of a parking garage in Lower Manhattan where federal agents were staging before an immigration raid targeting street vendors from West Africa, similar to a raid in October on Canal Street. This weekend, Time magazine ran a headline that read “How 200 New Yorkers Foiled an ICE Raid Before It Even Began.” You got there soon after this whole thing was happening, Murad. Your staff was there. Can you talk about what took place? And also, I mean, New York City is a sanctuary city. Police did make arrests, about a dozen people. Are they cooperating with the ICE agents?

MURAD AWAWDEH: So, last Saturday, you had over several dozen ICE agents who had been congregating in this garage facility. And I think people don’t realize how big and small New York City is. We are a city of 9 million people. We are across 300 square miles. And, you know, it is very hard not to be noticed, especially when you are about to do something that people in the city do not welcome. Several people witnessed this. It became several dozens after they put out the call, and then several hundred showed up to push back against them. And, in essence, these New Yorkers thwarted this and foiled this plot that they had of doing this mass theatrics on Canal Street yet again.

The problem with that is that when the protesters did arrive, what you ended up seeing was NYPD coming in to provide cover for ICE. And the way in which NYPD is reporting it is that they were doing crowd control and helping get them, quote-unquote, “out of the parking lot” so they can be on their way. There’s a very slippery slope here, where they’re operating in a gray area, where they did collude with ICE, even if it was for the crowd control in that moment.

But what does that mean for the future? What does that mean when NYPD shows up to an ICE raid, which has been happening across the city since the inception of this administration for the past 11 months? Just this morning in Jackson Heights, there was a massive raid. So, what does it mean when you’re having these instances where New Yorkers are going to stand up and nonviolently defend their community?

Can a Deal Be Reached to End Russia’s War in Ukraine? Matt Duss on Latest Diplomatic Efforts

This post was originally published on this site

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Matt Duss, you’re the executive vice president at the Center for International Policy and also former foreign policy adviser to Senator Bernie Sanders. We also want to ask you about the ongoing negotiations to end Russia’s war on Ukraine. On Tuesday, President Trump’s envoy Steve Witkoff and son-in-law Jared Kushner met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow for nearly five hours, but a deal to end the war in Ukraine was not reached. Russian officials described the talks as “constructive” but said no compromise was reached on certain issues.

AMY GOODMAN: Witkoff and Kushner are set to meet today with Ukraine’s lead negotiator in Florida for further talks. Meanwhile, Putin is now in India meeting with Prime Minister Narendra Modi. This all comes as Germany’s foreign minister has criticized Russia, saying he had seen no serious willingness on the Russian side to enter into negotiations. And NATO says, of course, that they’re going to continue to supply U.S. weapons — pay for and then supply U.S. weapons to Ukraine. Where does all this stand, Matt?

MATT DUSS: I think, well, I mean, first of all, I would say efforts to end this war through diplomacy are good, and I commend them. I think most Americans would like to see this war end. Certainly the Ukrainians want this war to end. The Europeans want this war to end. But once again, I think we have arrived at the same place, which is that Vladimir Putin does not want this war to end, certainly not on terms that would be remotely acceptable to Ukraine, by which I mean a resolution to this war that sustains and preserves Ukraine’s independence, its democracy and its ability to defend itself.

I think a lot of people were kind of surprised by the extent to which the 28-point plan that was leaked a few weeks ago really, essentially, you know, echoed Russia’s preferences. Some people said it was written in Russia. I don’t know if that’s true, but it clearly did reflect a lot of Vladimir Putin’s own preferences for how the war should end. As an opening bid, I don’t think we should make too much of it. It is good that these talks are going on. But again, I think we’ve arrived at the same place, which is that the person who has a very, very important vote here, Vladimir Putin, is not supporting an end to the war.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, it’s extraordinary, Matt, because I did read over those 28 points, and it does seem, as many have commented, that most of Russia’s demands have been met. So, what explains their resistance to this proposal? And what parts did they — do we know what they took umbrage with, that they don’t want to agree to?

MATT DUSS: Well, I think there are issues. You know, there was kind of a negotiation going on within the Trump administration. You know, Witkoff and Kushner put out this plan or were, you know, involved in constructing it initially. Secretary of State Rubio then made changes internally. There’s a kind of fight between the Rubio and the Vance wing in the Trump administration here, with the Vance wing being much more aggressively trying to end this war.

I think that some of the key concerns were the kind of agreement that Russia — excuse me, that Ukraine would not join NATO as a promise. Some people see that as unacceptable. Personally, my own view is everyone, I think, understands that Ukraine will not be joining NATO. I understand that you don’t want to take that off the table at the outset of negotiations, but I don’t think that should be — you know, that shouldn’t be allowed to be a roadblock to an agreement.

At the same time, I also don’t think that is the only thing that concerns Russia. As I said, Vladimir Putin’s goals here, in my view, have not changed. I’ve seen no evidence that his initial goal of curtailing Ukraine’s independence and bringing it back under, essentially, Russian authority as a part of a broader Russian imperium, that remains his ultimate goal. And any agreement short of that, it seems to me, he’s not going to go for.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And, in fact, on NATO, which, of course, many speculated that this was indeed the reason that Russia invaded Ukraine, it’s not only that the plan calls for an end to NATO expansion, but it says specifically, singling out Ukraine, that Ukraine should inscribe in its constitution that it will not join NATO, and that NATO would include in its statutes a provision that Ukraine will not be admitted. If you could —

MATT DUSS: Yeah.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: — comment on that?

MATT DUSS: Yeah, I think that that really just goes way, way too far. I think there are — there are commitments that could be made, assurances that could be made with regard to Ukraine and NATO. But again, I do not think that NATO and Ukraine’s possibility or impossibility of joining NATO is really the issue here. It is one among a whole set of issues that indicate Ukraine’s ultimate orientation and its ultimate independence. Ukraine’s independence is the real issue here, as far as I can tell.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And the plan also says that all parties to the conflict — I mean, Ukraine and Russia — will receive full amnesty once the proposal goes into effect, the ceasefire, if indeed that’s what it is, the peace plan, which seems, some have said, in part, geared towards having the ICC warrant against Putin lifted and also —

MATT DUSS: Yeah.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: — absolving Russia of alleged war crimes, including what happened in Bucha. If you could comment on that?

MATT DUSS: Yeah. I mean, that is — that’s really objectionable. But, you know, again, as hard as it is to say, if that’s something that gets us to an end to the war, a durable end to the war, that is something that we should consider. This is certainly not justice for the many, many victims of Russia’s violence, which has been grotesque.

Unfortunately, the United States itself is not in a great position here, given the cover that we continue to give to partners like Israel for their war crimes in Gaza, clearly war crimes. So, I think the United States and its allies in Europe would be in a much better position to push back against this if we were applying these standards equally, which we are not.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Matt Duss, the significance of the corruption scandal that’s been engulfing the Zelensky administration, with his number two man, Andriy Yermak, the chief of staff to Zelensky, being forced out? You usually always see him at his side.

MATT DUSS: Yeah, no, I think this has been a corruption scandal that has been brewing for a while, and the firing of Zelensky’s number two man, his chief of staff, is obviously very significant. Ukraine continues to struggle with corruption problems that go back a long time. But I also think it’s worth noting, the fact that the number two leader in Ukraine was removed from power because of a corruption investigation is itself a very, very positive step.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And finally, Matt, if you could comment on the sheer scale of the destruction that this war has wrought, not only in terms of, you know, entire areas in Ukraine being flattened, but also that Russia has suffered over 600,000 casualties? That is to say, people killed and wounded. This is roughly 10 times the number of Soviet casualties suffered over a decade in their invasion and occupation of Afghanistan. And open-source data has revealed that 111,000 Russian military personnel have been killed. Meanwhile, also open-source data shows that there have been about 400,000 Ukrainian casualties. And Zelensky himself has said that 43,000 Ukrainian soldiers have been killed. So, if you could talk about this? I mean, this is a really extraordinary — these are extraordinary numbers.

MATT DUSS: Yeah, it is extraordinary, and it’s just a staggering waste. I mean, for what? For what did these people die? For what reason were they sent into this horrible meat grinder? For what was this destruction done? To take some land in eastern Ukraine?

I think this is — again, as horrible as this is and as horrible it is to consider the fact that there might have to be some form of amnesty, I do also think it’s worth noting that Vladimir Putin, after nearly four years of war, has not achieved anything close to his ultimate goal. And I do think this is worth considering as we talk about the possibility of a ceasefire. Ukraine has performed far — has done greater things than I think anyone expected. So, given the loss of life, given the destruction, I know it’s hard for many Ukrainians to consider having to make some concessions to end the war, but I do think there is a victory narrative here for Ukraine to take.

One other thing I do want to mention in terms of the costs of this war is the tens of thousands of Ukrainian children that were taken into Russia and distributed among Russian families. That is absolutely something we should not forget. That is something on which there should be no compromise. These children need to be returned to their families.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And what does the — what does the plan say about that, the proposal that the U.S. has put forth?

MATT DUSS: I’m unclear what it says on that. This is something that’s clearly going to be contested as we get into the — if we get into anything close to final status talks, which it doesn’t seem like we’re close to right now.

AMY GOODMAN: Matt Duss, we want to thank you so much for being with us, executive vice president at the Center for International Policy and former foreign policy adviser to Senator Bernie Sanders.

This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. When we come back, President Trump says he’s going to limit immigration from, quote, “the Third World.” We’ll be back to talk about this and what’s happening here in New York City, ICE raids that have been thwarted by activists blocking ICE cars. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Malian musician Khaira Arby, performing in our Democracy Now! studio.

Will Hegseth Go? Defense Secretary Faces Anger from Congress over Boat Strikes, Signal Chat

This post was originally published on this site

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: The Pentagon’s inspector general is set to release a report today on Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s use of the widely available social media app Signal to discuss U.S. airstrikes in Yemen earlier this year. Two people familiar with the report’s findings told news outlets that Hegseth endangered U.S. troops in using Signal to discuss the strikes with several other senior Trump administration officials. The chat, which included Hegseth’s wife and brother, was revealed when The Atlantic’s editor Jeffrey Goldberg was accidentally added to the Signal group.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re joined now by Matt Duss, executive vice president at the Center for International Policy and former foreign policy adviser to Senator Bernie Sanders.

Matt, thanks so much for being with us. In a moment, we’re going to talk to you about the negotiations around Ukraine. But let’s start with this top news, and that is everything that’s happening right now with Pete Hegseth, the defense secretary, or, as he calls himself, the war secretary. If you can start off by talking about what’s going to be released today, but many news outlets have already reported on, saying that he shared sensitive information with a reporter and others about attacks on Yemen? Talk about the significance of this.

MATT DUSS: Right. This happened last year as strikes, U.S. strikes, on Yemen against Yemen’s Houthi government were about to begin. The Houthis, as people may remember, had been launching strikes on shipping in the Red Sea and on Israel in protest of the Gaza war. The U.S. was about to undertake strikes against the Houthis.

As you noted, the journalist Jeffrey Goldberg was included on a Signal chat of senior administration officials in which, apparently now, classified information was being shared by the secretary of defense, you know, including when the strikes would start and other things that he was not authorized to release. Now, the secretary of defense does have the authority to declassify information if he chooses, as does the president, but none of that, clearly, was done. This was just carelessness. It was reckless. And as the report is going to say, this potentially put U.S. troops and service members in danger.

AMY GOODMAN: And can you talk about the fact that Pete Hegseth refused to sit for an interview or hand over his phone? Is it just up to him, the man who is being investigated himself? And where does Roger Wicker, the head of the Senate Armed Services Committee, and Jack Reed stand on this in this investigation? What do you expect to take place?

MATT DUSS: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Could they force him?

MATT DUSS: Well, I think Pete Hegseth, much like the president he serves, sees himself as, essentially, above the law, as unconstrained by legal procedures, by his own obligations, apparently, to U.S. service members, given that he very clearly put them in danger. So, unfortunately, it’s not surprising that he would not sit for an interview.

This investigation was a form of oversight, an important form of oversight, but I do think the more important form will come when we see what Congress is going to do about it. You mentioned Senator Wicker, Senator Reed in the Senate Armed Service Services Committee. How far do they push this? How aggressively are they going to be toward the administration when this report comes out?

And I think the question really does come down to the Republicans, because, unfortunately, in general, the Republican leadership has been pretty subservient to Trump. They have not been all that willing to assert their oversight authority. But given the recklessness of this act and also some of these other things that have been piling up around Pete Hegseth, including the strikes on the alleged drug boats that he’s facing now, from what I’m hearing, Republican impatience toward him is really, really growing on the Hill, and this could be something that really pushes people over the edge. But we’ll have to see.

AMY GOODMAN: And very quickly, Matt, today, the Admiral Mitch Bradley is expected to testify before Congress about the second strike on that September 2nd boat, what the Trump administration calls “drug boats.” Of course, they have not presented any evidence. Nine people killed in the first strike, two hanging on for dear life, and they then killed them.

MATT DUSS: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: The significance of what this means and the overall attacks on the boats, as President Trump says they’re going to attack Venezuela directly imminently?

MATT DUSS: Right. Unfortunately, it seems that Pete Hegseth is using Admiral Bradley as a human shield here. We’ve seen, just over the past few days, trying to put blame — or not put blame. He’s trying to say, “I stand behind Bradley, who gave the order. I didn’t give the order.” They’ve had multiple stories about what happened, what didn’t happen, who gave the order.

But it is important to understand this is happening in a context of strikes that are not — clearly not in the context of war. They are unauthorized. As you noted, there has been no proof given that these are drug boats at all, that these people were engaged in anything illegal, and even if they were, it seems absolutely unnecessary to destroy these boats, to kill these men who have been convicted of no crime.

AMY GOODMAN: And, of course, not just unnecessary, but the question is if this is just outright —

MATT DUSS: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: — murder, if these are war crimes.

MATT DUSS: That’s right. Right.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, let me ask you about Admiral Alvin Holsey, the African American head of SOUTHCOM, the first Black head of SOUTHCOM, who’s out next week, but was forced out, apparently, in October after his objections to what’s going on with these boats being targeted. The significance of this?

MATT DUSS: Right. I mean, that happened — there was a wave of firings, essentially, early in the Trump administration, especially in DOD, a clearing out of senior leaders who were seen to be not with the program, essentially. And that seems to be what had happened here, discomfort with what was going to be a really aggressive policy toward Latin America. And that’s what we’re seeing play out.

But I do think, as you noted, while this is, you know, really, really, I would say, objectionable and clearly criminal, it does come in the context of years and decades of U.S. abuse and U.S. violations around the world. So, we need a deeper — we need to take a deeper look at the authorities that have been given and abused by successive administrations, not just this one.

Headlines for December 4, 2025

This post was originally published on this site

Democrats on the House Oversight Committee released more than 150 new photos and videos of the late convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein’s private island in the Caribbean. The images show a room with a dentist’s chair surrounded by masks, a bedroom, a palm tree-lined swimming pool, and several other living spaces. Democratic Congressmember Robert Garcia, a ranking member on the House Oversight Committee, said, “These new images are a disturbing look into the world of Jeffrey Epstein and his island. We are releasing these photos and videos to ensure public transparency in our investigation and to help piece together the full picture of Epstein’s horrific crimes. We won’t stop fighting until we deliver justice for the survivors.”

Meanwhile, Epstein’s co-conspirator Ghislaine Maxwell, who is currently serving a 20-year sentence for sex trafficking, is planning to ask a court to release her — that’s according to a letter filed at a federal court in Manhattan. Earlier this year, Maxwell was transferred from a federal prison in Florida to a minimum-security camp in Texas about a week after she spoke with Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche, who is one of President Trump’s former lawyers.

“WTO/99” Filmmaker on Anti-Corporate Globalization Movement: “These Issues Haven’t Gone Away”

This post was originally published on this site

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

We end today’s show with a new immersive archival documentary about the historic 1999 protests in Seattle against the World Trade Organization, corporate power and economic globalization. The film’s scenes of the militarized police response and National Guard troops in the streets of Seattle seem eerily familiar. It uses more than a thousand hours of footage from the Independent Media Center and other archives.

This is the trailer for WTO/99.

DAN RATHER: One hundred thirty-five nations are gathering in Seattle for the World Trade Organization meeting.

PROTESTER 1: The TV stations, they’re not informing people why there is a protest. This explains why there is a protest.

PROTESTER 2: My personal reason for marching is I want to see fair labor practices.

PROTESTER 3: Globalization has already gone too far.

PROTESTER 4: Not in our city! Not in our state!

PROTESTER 5: By nonviolently shutting down the World Trade Organization.

PROTESTER 6: I don’t think they understood there were really going to be 70,000 people.

POLICE OFFICER: If we’re going to clear this, we’re going to need at least five more squads.

PROTESTER 5: The police are protecting millionaires who are killing our environment, our future and our kids.

MAYOR PAUL SCHELL: This is the last thing I want to do, is be a mayor of a city where I had to call the National Guard.

PROTESTER 5: You have the right to be here. Raise your hand if you care.

AMY GOODMAN: Before the 1999 protests, Congress debated a bill to support the creation of the World Trade Organization as an international judicial body to govern global trade. This is Senator Bernie Sanders at the time in another clip from WTO/99.

REP. BERNIE SANDERS: I think there is an important issue of sovereignty. The American people are increasingly alienated from the political process. And the World Trade Organization only takes more and more power out of the hands of local government and state government, and it gives it to nameless bureaucracies abroad that operate in secrecy.

AMY GOODMAN: When more than 40,000 people tried to shut down the WTO meeting in Seattle, they used nonviolent direct action but were met with massive amounts of tear gas. In this clip from WTO/99, we hear a police announcement to protesters.

POLICE OFFICER: Seattle Police Department. You are being ordered to leave the area. Go westbound on Pike, and go north on 6th. We are going to start using chemical agents now.

AMY GOODMAN: Democracy Now! was in the streets of Seattle. One scene in WTO/99 features my questioning of a Seattle police lieutenant wearing a gas mask.

AMY GOODMAN: Lieutenant Sanford, the person with the orange gun, that’s rubber bullets?

LT. SANFORD: I have to be honest. I don’t know what’s in it. I would have to ask him specifically.

AMY GOODMAN: Could you ask him?

LT. SANFORD: I could. It’s probably either chemical agents or rubber bullets, something like that.

AMY GOODMAN: Could you ask? Just wanted to know what it is.

LT. SANFORD: Sure.

AMY GOODMAN: Thanks.

POLICE OFFICER: Let’s have you scoot back. Scoot back, please.

AMY GOODMAN: Yeah.

LT. SANFORD: It has a whole variety of things that go in it.

AMY GOODMAN: You mean, could it have chemical agents and rubber bullets together?

LT. SANFORD: Absolutely.

AMY GOODMAN: Despite the police crackdown, protesters in Seattle had an overwhelming sense of victory. A dramatic scene in WTO/99 features legendary consumer advocate Ralph Nader.

RALPH NADER: Thank you. Thank you very much.

PROTESTER: Run for president!

RALPH NADER: I’m sure you realize what a historic week this is here in Seattle. And I’m sure you realize that never before in American history has any — has any cause for justice brought together so many people from so many different occupations and backgrounds. Why? Why is it that although there are all — a lot of the groups represented here often disagree with one another on a daily basis — why is it they’re all together on this? Because the World Trade Organization is a principal threat to democracy in the world.

AMY GOODMAN: Scenes from the new documentary WTO/99, which starts screening this Friday at DCTV here in New York City at the Firehouse Cinema. We’re joined now by the film’s director, Ian Bell. Ralph Nader is still with us.

Ian, talk about why you’ve taken this on, what, more than a quarter of a century later. Talk about this, really, archival extravaganza that documents what happened on the ground in Seattle.

IAN BELL: So, we took this on from — kind of came from a number of conversations me and my editing partner were having around the 2016 election. We were really interested to see if there were deeper seeds to the shifts of the labor vote, and thought that maybe we could learn a little bit about going back to WTO and the events of 1999.

The film really started when we came across a project that was happening in Seattle of the organization and digitization of the Independent Media Center footage. An organization called MIPoPS was digitizing about 400 hours. And we were lucky enough to connect with them in the middle of that project and ultimately get the access to that footage after they were finished.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Ian, you mentioned the Independent Media Centers, but really the WTO protests were perhaps the birth of citizen journalism on a mass scale. The importance of having all of this archival footage? And could you talk, for those people who don’t know or weren’t around then, the importance of the IMCs and how that movement spread across the country and the world?

IAN BELL: Yeah. One thing that we were really struck by was, you know, small digicams were becoming more ubiquitous in the late ’90s, and because of this technology and the efforts of the IMC at the time, we have all this footage that has been preserved by people in their shoe boxes, people collecting them and gathering them together and then ultimately giving them to archivists. And what’s so important about what they did was we’re able to — and you see it in the film — we’re able to see the events as they unfolded on the ground, as people who were in the crowds were seeing it, watching the interactions between protesters and the police. And the footage covered the whole week, almost every minute of the week. And we’re able to then cut that together and compare it to the way it was being covered by local media.

And I think what IMC — the real gift that the IMC provided to us, who now — you know, in the future, is seeing that local media wasn’t up to the task to show the people at home what was unfolding. And we’re able to cut between those two sources, including national and international news, in real time to give people a sense of the narratives that were being constructed by those who maybe weren’t asking the right questions or any questions, or weren’t curious enough to know exactly why people were coming to the streets.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Ralph Nader, looking back now, more than 25 years, a quarter of a century, the importance of those WTO protests in terms of shaping movements for progress and for radical change in the United States?

RALPH NADER: It punctured the myth of free trade. It wasn’t free trade between countries. It was corporate-managed trade that went beyond trade to subordinate higher standards for consumer, labor, environment and make them viewed as nontariff trade barriers, and therefore illegal. So, this is — these are pull-down trade agreements, enforced by WTO and NAFTA, and the Seattle protests blew that out of the water. And it began a change in Congress to eventually get us out of even worse entanglements, like the Pacific trade agreement, even before Trump took the issue away from the Democrats and ran with it.

AMY GOODMAN: Ralph, I wanted to go to one of the large corporations that were targeted there, in addition to the WTO. The film shows protesters targeting Starbucks’ flagship location on 9th and Pike in Seattle, then a clip of local news coverage featuring the response of then-46-year-old Starbucks Coffee CEO Howard Schultz.

ANCHOR: Howard Schultz says he can’t figure out why one of his stores was targeted. We talked with him at last night’s Sonics game.

HOWARD SCHULTZ: We’ve really tried, as a business, to develop a corporate conscience, not only domestically, but around the world, especially where we buy coffee. So, to hit Starbucks, really, we have to question why.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s so interesting, Ian Bell. In this last 30 seconds, we just covered a protest outside Starbucks in Brooklyn, tomorrow a major one outside the Empire State Building. Mahmood Mamdani, right? I mean, Zohran Mamdani, the mayor-elect of New York City, and Bernie Sanders were both there. The significance of 26 years ago and today, as we end this conversation?