Wake up, Maggie. I think I have something to say to you

This post was originally published on this site

This Saturday marks one year since my mother died. I did not write an obituary for her when she passed. That has haunted me because in another chapter of my life as a news writer, I wrote hundreds of obituaries. So, seeing that March is meant to be a national celebration of women’s history, I suppose the timing is just right.

Maggie Buchman was a hell of a woman. And her history may not be known to the world, but I will celebrate it for the rest of my days.

This is not a traditional-style obituary because my mother was not the traditional type. Instead, this is a letter. Like one of many I wrote her over the years.

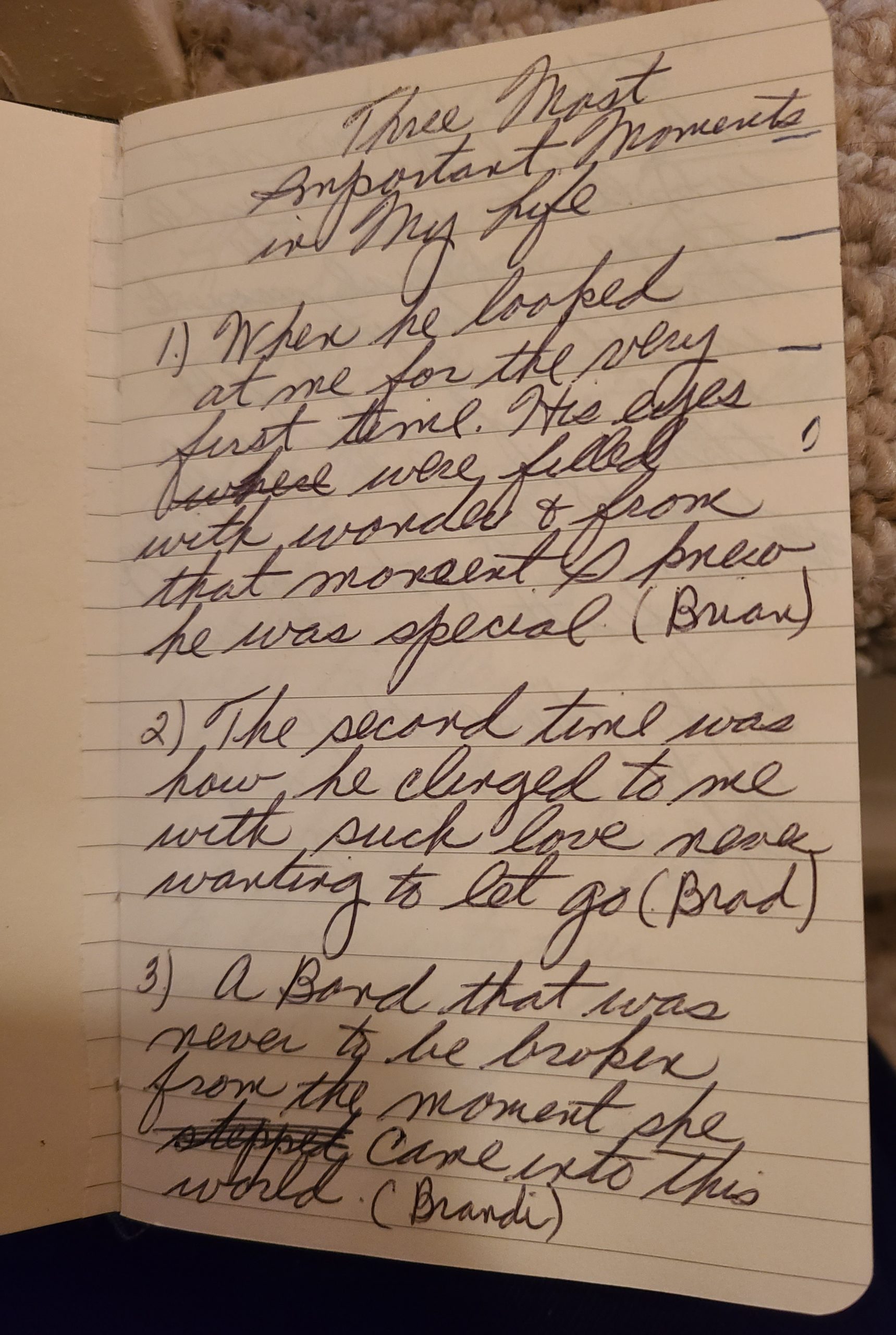

“The boys,” by the way, were what we called my brothers.

March 19, 2022

Well, Mama.

I didn’t think I’d make it.

I sat in that chair out back a year ago staring through branches just hoping the universe would strike me down right then and there. My chest was so tight, that I tell you with no exaggeration, I was certain I was having a heart attack.

And the scary part, Ma? I didn’t care.

I hoped it was a heart attack. I can hear you now, but I wanted to lay down and die. Not the love for the boys, not the love for myself, not friends, no one. Not my gig, life’s art, or its beauty. Not the simple open-ended bounty of just drawing breath—none of it, Ma.

The idea of slogging out day after day for an indeterminate period of time on this forsaken rock without you, the other half of my whole heart, was beyond crushing.

A year has come and gone. I’m less ready to die. I see with greater clarity now that I was tired. So tired.

For the record, I would have done it all over again for you: walked through the exhausting hell that is a slow, painful death. In the end, it really was exactly how you always told me.

“There’s no hell with fire and brimstone, baby. It’s up here with you and me.”

So, here I am in hell. Or some sort of in-between, walking slightly dazed—still—in the gigantic wake of your death. Getting on day by day, and I can’t believe there’s been over 300 of them. The yawning maw of hundreds, thousands more to come maybe, I confess, is daunting.

Not one has passed where I have not thought of you. And many of our moments together. But I have been stuck on a final gift you gave me as you made your exit: liberation.

Unironically, it’s the same gift you presented to me every day, with a boundless optimism, from the time you were young.

Ma, wait. Can we relish that for a moment? Young Maggie. Healthy. Spry. Always tan. A smile that could knock out a streetlight. To be fair, that smile lasted until the end. So did the softness of your skin, from as far back as the boys and I can remember. Skin so soft, so impossibly, impeccably soft. Always smelling of perfume. The curls about your face. The impossible twinkle in your eyes. I miss your eyes. Hazel with indigo gray around the edges.

Mama, here is your legacy.

You died a free woman, at 74 years old, all of life’s meaningless refinery stripped from you. Just you, me, and the boys by your side. To the end. As promised. Though you never needed to ask.

You lived your life how you saw fit. You guided your moments overwhelmingly by a motivation to do right by your children, but your view was never so narrow that your compassion limited itself to just your tribe.

You made mistakes, you misjudged. At times, you were gullible and as a result, vulnerable, because the benefit of the doubt you gave was so large, so perpetual, it clouded even more reasonable limits of self preservation.

But generosity is no weakness. You taught me that. The wise know that. On a daily basis, you drew from a place in your heart—a place I gazed into a million times—that understood existence is fleeting, so cruelty truly is a pointless endeavor pursued only by the weak and fearful.

You died a free woman even though your body imprisoned you—a fate that, to varying degrees, awaits us all. But you rattled your cage, sure enough, holding on weeks longer than any doctor deemed typical.

Speaking of, Ma, if us Buchmans weren’t built for feats of endurance, I swear I don’t know who is.

You died a free woman because your mind was free, your spirit was free. Cancer didn’t change the core of who you were. It just stole your body.

Your death was never going to be easy on us and you knew that. But even with that, Ma, I want you to know that for as bad as you felt, for all the misplaced guilt you had in the end about us watching you die as we shepherded you away, Ma, I promise you this: Seeing life so up close at the end freed me.

I am freer today because I know if I could survive that, I could survive anything. No philosopher, priest, or proselytizer could have made the argument better than you did with your death.

Your life was a long series of sacrifices for us kids. I want you to know, and anyone reading this, that none were made in vain.

Thanks, Mama. Miss you like crazy.

P.S.

We both know I’m the most gorgeous one but we’ll let Brad have this one.